In February 2022, I found by way of an influencer that there was a shortage of a certain type of €8 water shoes. It was a funny thing to think of — did the brand run a small batch at that time of the year? Or was the entire northern hemisphere just swimming places in winter? In the same shoes? How solidary.

In May that year, the Strategist picked up the story and did its cute bit of US-centric research, but the results remained inconclusive. Finally, they blamed the ordeal on PVC supply-chain issues brought about by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This, these shoes, were now a global issue.

Two things stayed with me: one, judging by rhythm alone, the senior editor who wrote that article was out of breath the entire time; and two, to my housebound mind, those shoes — blue and clear, holes where you need them — were the emfootment of freedom. What you absolutely need to have around when one day, weather permitting, you’ll make your escape from the pervasive ‘this.’ Shoe-hope in a box. Otherwise, the hype was just too much to make sense. I have them, they’re alright — but, I mean, they’re water shoes.

Last week, at a party, I brought up the shoes to a bunch of people I’d just met, in the context of swimming, sea urchins and whatever else can cut a mean gash underwater; I stopped halfway through, and the story fell flat, of course, since at that point, it was. I wondered if they thought I was stupid.

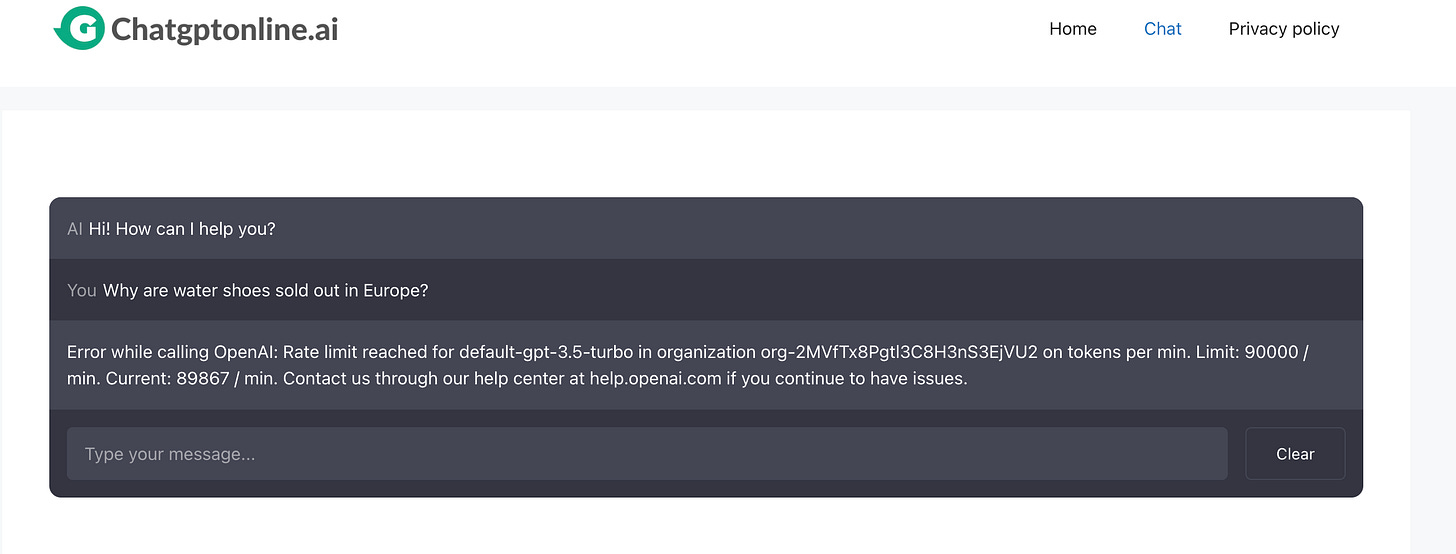

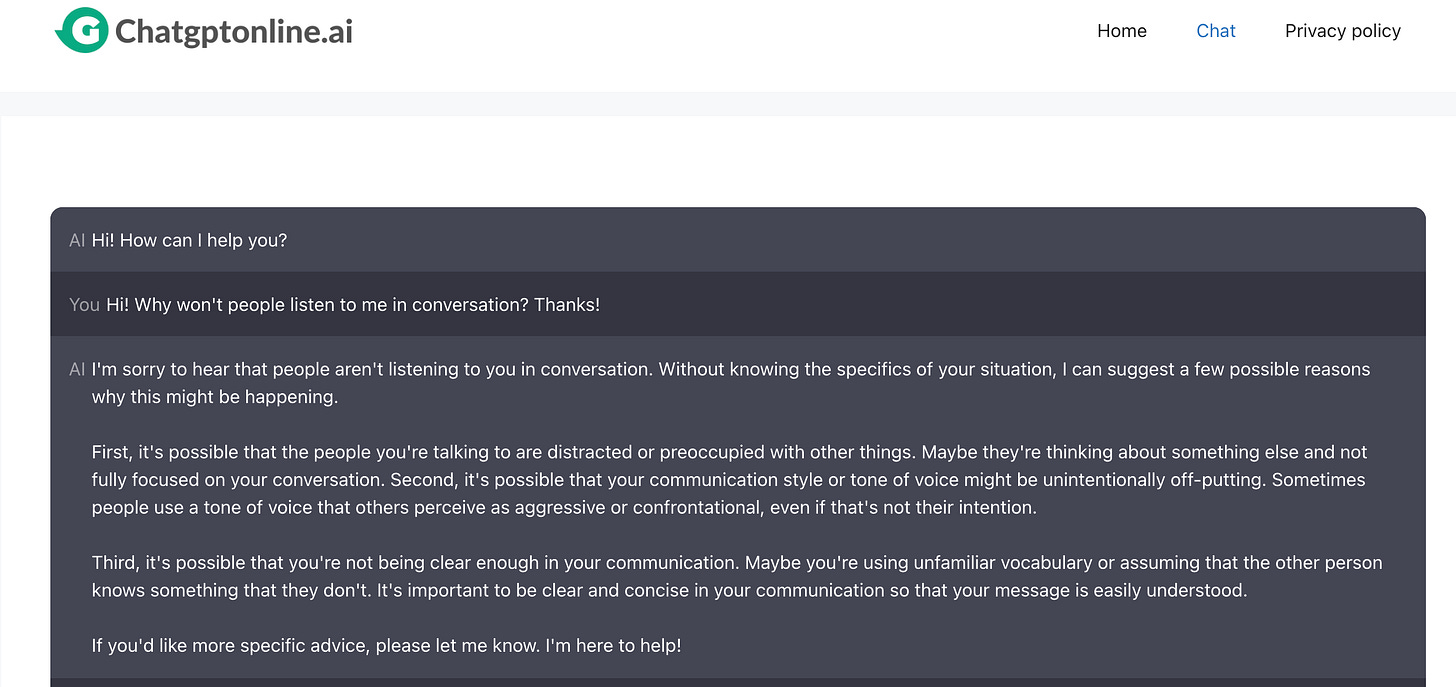

That’s fine, since going ahead with it might’ve made me seem boring. Anyway, I’ve always found talking a far more restrictive medium than writing, so, hi. My point now is this: the way this story makes sense to me may not may sense to you. And it certainly doesn’t make that sort of sense to ChatGPT (yet). Here, I asked it:

Understandable, I reached out at naptime. I tried again, and this time, in true human fashion, I did a quick attack on my subject, causing panic within myself when realising that I’ve asked an incomplete question the wrong way, so I rewrote it to be both specific and polite (two things that you can never go wrong with when it comes to robots — now and, you know, later). It worked.

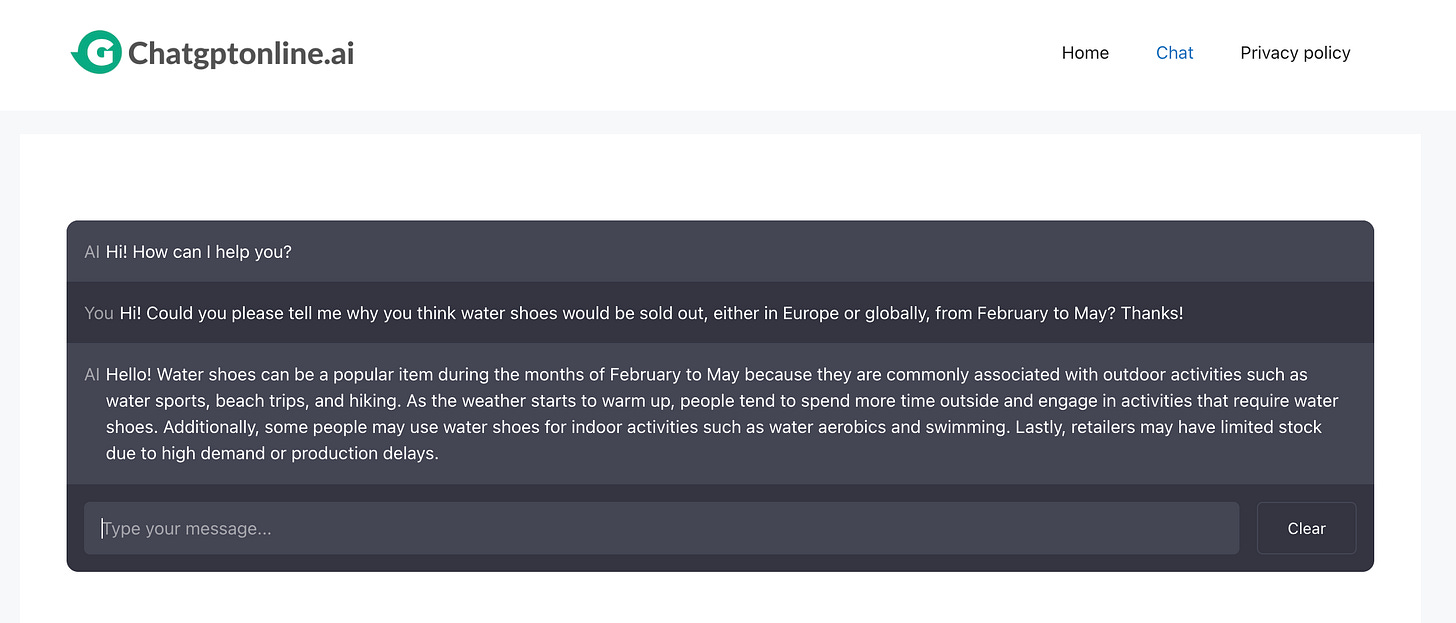

Unsurprisingly, the answer was formulaic, but wider in scope than that of the Strategist editor. It lacked the casual touch of sentience (no use of “we” in the sense of “myself and other algorithms” looked this up for you, no judgmental collocations, no ageist nuance), but it did the job: it conveyed a piece of banal information for what it was. I respect that. It’s refreshing.

There’s no emfootment, though; no freedom, no shoe-hope, no ‘this’. Evidently, we don’t see eye to AI (yet).

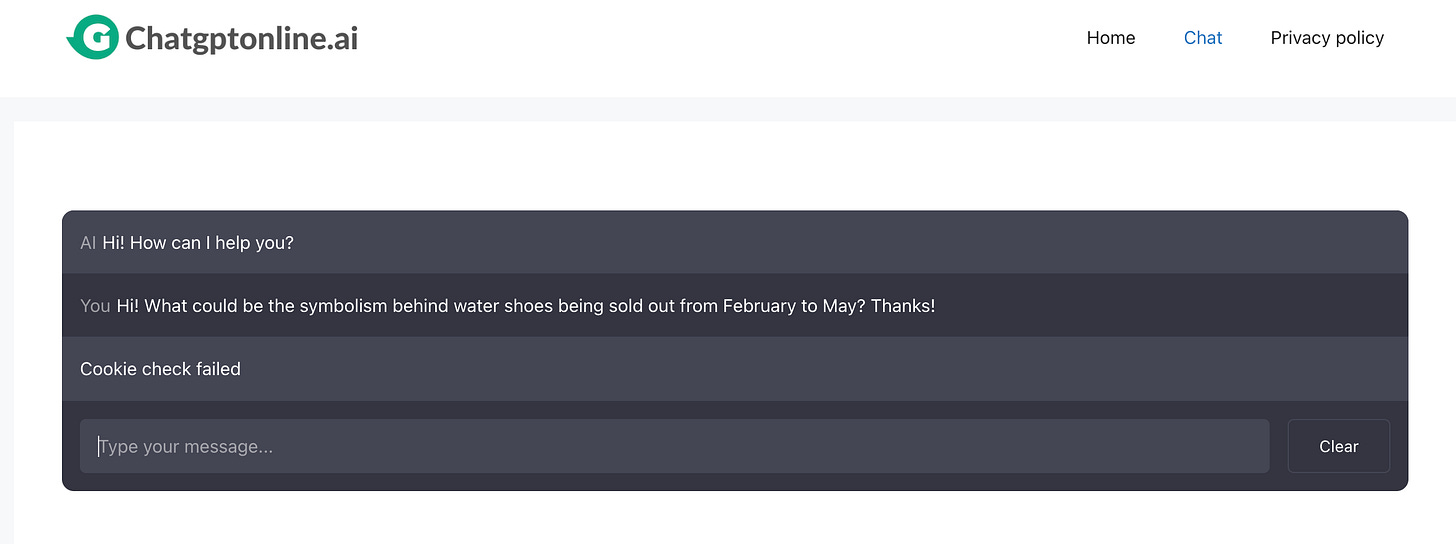

Fair. I should’ve brought treats. I wonder if this was its first attempt at asking for better pay.

This is generative AI and the creative world fears it. Since August 2022, Tim Boucher used ChatGPT, Midjourney and Claude to write 97 e-books in 9 months and sold 574 copies; how will this redefine the fiction market for us guppies, or even for big fish like Haruki Murakami, who took six years before publishing “The City and Its Uncertain Walls”, and is said to write 1,600 words a day? Or for Hanif Kureishi, who would take about 3-5 years to publish a new novel, and would churn about 1000 words a week — all before his accident in January, which left him unable to move his arms and legs? Their reputation notwithstanding, in this context, AI feels daunting to compete with— until we look at originality (defined as the ability to think independently and creatively) and word count.“The City and Its Uncertain Walls” is about 297,500 words long. Kureishi’s “The Buddha of Suburbia” is about 80,000. Boucher’s books are all between 2,000 to 5,000 words long and “all cross-reference each other, creating a web of interconnected narratives,” which he argues, twice, keeps the readers curious and engaged and hungry for more.

Alright. So, what AI’s done is a quick fetch-and-spew of readily deducible information. Historically, this has been lucrative, since human audiences tend to reach out to what they’ve seen, read, watched or heard before, and consequently, what packs the most familiar punch for the least amount of energy expended. The trouble here is that this is what many writers have also been consistently asked to cater to, to the detriment of creative evolution. In Boucher’s words, “People enjoy coming back to the same story-worlds again and again.” You don’t call an emerging battle that which has already been won. AI’s got this.

Are writers now free to take a different angle? Is anyone even interested? I cut my shoe story short that day because I wasn’t sure anyone would listen. For some years now, but unmistakably so in the past six months, in settings where the primary point of focus is conversation, I get about two phrases in before people look away, start a whole other conversation with each other or just gravitate back to their phones. This, I found, happens mainly when my contribution becomes unrelatable; this, usually, comes after everyone else has said what they had to say. At very basic levels, it seems, few people around me are actually paying attention. ChatGPT gets it and, endearingly, it’s the first to apologise.

Alright. I’ve got to be nice, get to the point, keep it fun and make it easy. It’s as if this robot knew I’m a woman.

Fine, I’m boring. But what’s boring in the context of our current attention spans?

We’ve come to a point where our social functioning is impaired by the rules of digital entertainment we play by, and the cognitive degradation this has generated. At their most complex, our brains are pretty simple. Our conscious mind is only capable of one, maybe two thoughts at a time. What we do when consuming multiple media forms at once is to delude ourselves that we can actually handle them simultaneously. In describing the switch-cost effect, Professor Earl Miller, an MIT neuroscientist, argues that this is not the case: we are only going back and forth between tasks and reconfiguring our brains in the process. This isn’t seamless. This slows us down. “It seems to me,” he says, “that almost all of us are currently losing that 20% of our brainpower, almost all the time.” Makes sense.

We used to worry, I remember, about our attention spans. At first, how it was an individual problem of varying proportions, and more than just moral panic. Then, it became a social phenomenon, too overwhelming, as they all are, to resist. With our diminished focus, everything comes into play, Johann Hari argues: from low-quality food to air to long working hours to lack of sleep and the hours of play we deny our children and how education’s stripped of meaning. We can put our phones away, sure, former Google Engineer James Williams told Hari, “but it’s not sustainable, and it doesn’t address the systemic issues.”

Have we given up trying to pay attention, then? Six years ago, in Facebook group tests, Fors Marsh estimated that people spent an average of 1.7 seconds with a piece of News Feed content on their mobiles. Best I can do with my shoe story is to mime it in two seconds: shoes, water, wear. From TikTok, ironically, hope: it takes Khaby Lame about 30 seconds to humorously re-simplify mundane situations which others have taken creative liberties with. He’s got 160 million followers. So, as long as it’s short, simple and similar to what we’re used to, people are here for it. In droves. Anything else?

Yes. That collective obsession with spinoffs.

Sure, we can still sit down and watch a show that’s another show. Once in a while, we’ll even stream a whole new movie that’s just like another we’ve seen before. It’s not an illusion of memory, it’s as preordained as a ChatGPT sermon: our cumulative entertainment choices have left us with little viewing choice at all. With the mere-exposure effect always in full swing, our predilection to give our undivided attention to what’s familiar has paved the way for media franchises like Marvel, for one, to “swallow the film industry whole.” It puts out content every few weeks and its universe is as frictionless as iPads. In it, high-caliber talent meets macro-budgets and the promise of relevance — in the words of Angela Bassett, “a winning formula.”

What screenwriters have recently been denouncing, then, is not just low pay, but the insistence of TV executives to keep churning out spinoffs. Consider the similarities between “Everything Everywhere All at Once” and the origin Avenger story, Schulman argues for The New Yorker. Consider what mass preference for Thor has done to mid-range comedies like ____ at the box office. I’d consider it better if I could name one.

This is AI territory. Our behaviour, as an audience, has laid it out. When every viral video or massively successful film or bestselling book is predictable down to a T, is it any wonder that AI is having a field trip? Let it have it. Let us have it. It provides exactly what we, collectively, have come to ask for and corporations would benefit from. Uniformity has been a driving force which we have all fallen into like a trap, then some sobered up and exploited. It is hypocritical to act surprised.

To each their own but there’s room for more.

And there must be good money in it for those who make it. The room, and the more. Allow me my ignorance, but what generative AI can’t do (yet) is write the stories whose beginnings we’ve never told. Predict the spontaneous associations we make along the way but keep to ourselves. Describe the way the world and our interaction with it plays in our mind, often uniquely so. How Gabriel García Márquez surrounded the character of Mauricio Babilonia with yellow butterflies because it reminded him of an electrician who’d come to fix the fuse box at his grandparents’ house in Aracataca when he was a child; in those days, Marquez would find his grandmother chasing off a yellow butterfly with a kitchen rag, saying: “Every time this man comes to the house, the yellow butterfly comes along, too.”1 This wasn’t merely a symbol of hope, love and peace, like shown in Disney’s Encanto or described on every other blog. This was more. AI couldn’t have known, till now, that one of my primary-school students imagined her height as an infant as measured not in centimetres or inches, but in the length of small wooden spoons — “Not the smallest one, the second small, that’s it. That was me.”

We lose patience with things like that. We strip stories of the flavour of arbitrary details. But what would Olive Kitteridge be without the belching? Would the novel have gotten the Pulitzer, or the miniseries received 31 awards out of 35 nominations if the story hadn’t been so richly dysfunctional? What is it, then? Do we reward or debug the experience of being human? Sure, the latter works splendidly when applied to cancer prevention — not quite so in conversation, art, film and literature. We can give AI its share, let it help, but we must keep the space and be allowed the time to explore our subpar states; how our internal parameters are out of whack, how our errors are multiple but we don’t always observe them, and when we do, we don’t take the time to convert our losses to updates. They’re just losses.

Part of being sentient is a constant state of glitching because being sentient is hard. We glitch into love and daydreaming but also anxiety, addiction, destructive behaviours, missed connections and the ‘what ifs’. Sometimes, we choose to stay there and not step away. The best algorithms do a lot of that, too, get lost, but are then given their own landscape where they explore dozens to billions of parameters to varying degrees of meticulosity to make the best possible decision compared to other possible decisions, and generate an output, all without having to worry about feeding their kids. As a human being, who has the time or capacity for that?

The algorithms are happy to work with volume. Let them.

But let’s be specific about where they pull data from, ask for permission to pull it, pay the people who hold the copyright on said data, and remain transparent about their output, and where this is a good fit — not just in terms of bottom lines, but of social value added. Let’s push for regulation in spite of corporate threats, and not just fall for the pretence that AI is what everybody wants, can self-regulate, and it’s here to improve and not remove. OpenAI CEO may claim that, because it is his profit-seeking position to do so, but I have not met an actual developer who ever denied themselves their own humanity, however pleased they were with their own algorithmic creation. At the end of the day, they still kept their soft bits and read paperbacks. Where we go, collectively, algorithms go, so we’d better pay attention. That way, hopefully, we, on the receiving end, won’t pay for them to go there.

Mendoza, P. A. (2002). Profesiunea. In Parfumul de guayaba: convorbiri cu Gabriel Garcia Marquez. (p. 31). Curtea Veche Publishing.